- see also

Distillation of Alcohol and Denaturing by FB Wright, 1907 - available as a free download.

If you're looking for a supplier of small needle valves to use in these stills, try either hardware shops, or supliers of gas fittings for BBQ's or camping equip.

Pot Still Designs

There don't seem to be many instructions around for how to build

pot stills. I guess this could be because there are just so many

ways, and it really depends on what you have available to you. One

factor to consider is the angle of the lyne arm. Even with a pot

still you get a little bit of vapour condensing on the head &

arm, and running back down into the pot as a bit of reflux.

Depending on how much internal reflux is going on, the flavour will

vary. An upward sloping arm will cause much to run back into the

pot, thus cleaning & lightening the vapour more, whereas a

downward sloping arm will send all the vapour towards the jar, and

you'll collect a heavier flavour. See my Photos of Distilleries and Photos of Stills sold commercially pages to see what

variations in this are around in commercial distilleries, and Portugese Copper Alambics and Alquitars. Some also

have a bulge in the head. This constriction then expansion causes

some of the vapour to drop out, and again increases the reflux, and

lightens the spirit.

Jack writes ...

For a potstill, I've found that

the lyne arm (as it comes off the still body) should go up at a

45degree angle for 2 feet, then it should drop into the condensor.

The diameter of the tubing depends on the heat - for most stovetop

models (typically built out of a pressure cooker) 1/4 to 1/2inch

tubing is used for the lyne arm and the condensor. The narrower the

tubing is, the lower the heat setting you need to use. The

condensor running off of your potstill can be whatever diameter you

have (provided it's no smaller than 1/4"). Also, remember that you

don't have to have a coiled-tube condensor- you can use a jacketed

model just as easily. With stovetop potstills there is a lot of

room to adjust the materials dimensions, because the heat source is

so easily adjusted.

Wal elaborates ...

The shape and height has an effect

on flavor.

- Traditional Alambic. This is descended from stills used by

alchemists. It consists of a domed cylindrical boiler with a

bulbous still head. It sits in a brick furnace. From the still

header chamber, the lyne arm usually slopes downwards or is

U-shaped ('Swan's Neck'). The condenser is a coil in a tank of

water. Raki stills, moonshine stills and the 'Alambic Charentais'

for making cognac are examples.

- Varied Boiler shapes.

- Conical, classic whisky pot still ('Springbank'

whisky)

- Onion shape, slightly fatter than the classic shape

('Glenlivet' whisky)

- Pear shape ('Vintage Islay' whisky)

- Varied Neck (Column) shapes and heights.

- Conical column from boiler. The smallest whisky stills are at

'Edradour'and the tallest at 'Jura', 'Bruichladdin', 'Glenfardas'.

The stills at 'Glenmorangie' whisky distillery are ex gin stills

and are the tallest at 5.3m

- Boil ball and conical column ('Strathmill' whisky)

- Boil ball and cylindrical neck ('Lomond Still')

- Additional reflux feature in column. Column length and the

Milton Ball header chamber create reflux, but some necks are cooled

with running water to increase reflux ('Fettercairn' whisky). The

traditional Australian brandy pot still has a 'Brandy Ball' water

jacket at the top of the column. All are open columns. The 'Lomond

Still' has 3 adjustable plates and is used as a wash still at

'Scapa' whisky distillery.

- Carterhead Still. The column contains a basket holding the gin

botanicals ('Bombay Sapphire' gin')

- Varied Lyne Arms.

- Horizontal

- 30 degree downward slope

- 30 degree upward slope ('Deanston' whisky)

- U-shaped or'Swan's Neck'.'Alambic Charentais' for cognac,

'Plymouth' gin', 'Talisker' whisky, 'Lagavulin' whisky.

Ian Wisniewski's article "Still Very Important" in "Whisky Magazine" describes in

more detail how the shape of the still can affect the flavour...

Big thanks to Whisky Magazine for permission

to reprint the following

Knowing that stills of a certain size and

shape yield spirit with a particular flavour profile is all very

well, but applying this knowledge the other way around is far more

challenging. In fact, designing stills in order to produce a spirit

with specific characteristics is merely a starting point, as this

is only one factor in a complex (and not always fully understood)

equation, which also includes the spirit cut, heating method, rate

of distillation and type of condenser.

Even the relationship between the wash and

spirit stills is difficult to quantify beyond stating that new make

spirit is shaped by wash stills and refined by spirit stills. But

if the low wines aren’t right, the spirit stills can’t

correct them (and if fermentation is mismanaged, distillation

can’t fix that either).

(snip)

As the degree of reflux (condensation) is a

key factor in establishing the profile of the spirit, the length of

the neck is an important consideration. The taller the still, the

greater the degree of reflux. This is because heavier, denser,

oilier flavour compounds have a higher boiling point than lighter

flavour compounds and as they rise up the still the temperature

becomes relatively cooler, which means they condense and return to

the boil pot (base).

(snip)

As a shorter neck means less temperature

variation, there is consequently less reflux. This promotes the

progress of heavier flavour compounds into the condenser, yielding

fuller-bodied spirit, with a creamier, earthier, oilier

texture.

But size doesn’t always matter, as

reflux can also be enhanced by customising stills with various

matching accessories, including a boil bowl, pinched waist or flat

top, while cooling the neck of the still is another

option.

A traditional (cynical) explanation for a

flat topped still has been the low ceiling it had to squeeze under.

However, the technical influence of a flat top, as at Cragganmore,

results in a slightly higher degree of reflux because the progress

of vapours is not as gradual or progressive as it is with a swan

neck.

A pinched waist (as though a corset had been

tightened around the still), can be seen in The Glenlivet’s

wash and spirit stills. By reducing the surface area available to

the vapours (by about two-thirds at The Glenlivet), a pinched waist

initially accelerates the progress of vapours into the neck. The

subsequent, sudden widening of the neck, and relatively cooler

temperature, consequently increases reflux.

A boil bowl (bulbous section between the boil

pot and neck) can vary from being mildly to acutely convex (the

more convex, the more reflux). When vapours carrying heavier

flavour compounds expand into this larger, relatively cooler area,

they condense and return to the boil pot.

Dalmore Distillery effectively doubles up by

having a cooling jacket (also known as a water jacket) between the

boil bowl and neck of the spirit still through which cold water

circulates (using the same water source as for the condenser). This

practise dates from 1839, with the oldest jacket still in active

service dating from 1874.

At Fettercairn a different approach yields a

similar result. From a circular pipe located at the top of the

spirit still, cold water runs along the neck and collects in a

trough fitted around the still (from which it also drains). This

has the effect of “giving the vapours inside a little

fright” according to Distillery Manager Willie Tait. His more

technical explanation is that cooling a fairly short neck gives it

the effect of being much taller.

While purifiers are rarely seen, this is a

feature of Glen Grant’s wash and spirit stills. As vapours

leave the still and enter a copper pipe in a tank cooled by water,

lighter elements within the vapour continue onto the condenser

while heavier elements return to the still via another pipe.

Without this proceedure Glen Grant’s new make spirit would be

oilier and heavier, says Chivas Brothers’ Brand Ambassador

Jim Cryle. Similarly, in the opinion of Site Manager John Reid, a

purifier in the spirit still increases the buttery, creamy notes of

Edradour’s new make spirit.

But just as important as design features that

make a still unique, is the manner in which the still is employed.

Pungent, fruity esters are more evident in spirit collected between

68 and 72% abv, while a spirit cut extending to around 58% abv

includes heavier, oilier, fatty acids. Consequently, altering or

separating the spirit cut into batches collected at different

strengths would enable varying styles of whisky to be produced from

the same still.

(snip)

How [heating] is utilised also affects the

degree of reflux. Heating the still more rapidly increases the rate

of distillation, driving off vapours more readily. As this reduces

the degree of reflux, it promotes a higher proportion of heavier

flavour compounds. Driving vapours more rapidly also entails the

risk of carrying over some undistilled liquid, showing as a sour

note in new make spirit. Correspondingly, a lower temperature means

a slower rate of distillation, more reflux and a lighter (some say

finer) spirit. At the leisurely end of the scale this means

collecting around nine litres of spirit per minute, compared to

around 20 litres per minute in the fast lane. Additional reflux can

also be prompted en route to the condenser, using a lye pipe (or

lyne arm) extending at an incline, which drives heavier flavour

compounds back into the still.

By providing a greater surface area than a

typical worm, a modern ‘shell and tube’ condenser

increases the degree of contact between the spirit and copper,

helping to strip out meaty, sulphurous compounds. However, worms (a

coiled copper pipe of decreasing diameter, set in a worm tub with

cold water) do not neccessarily result in a higher level of

sulphurous, meaty flavours and the challenge lies in controlling

the level of these characteristics to achieve a complex

whisky.

(snip)

So, knowing these principles, is it possible

to quantify the importance of the stills within the production

cycle? Well not easily, that’s for sure. Beyond the usual 60%

of the malt’s eventual flavour being attributed to

maturation, I’ll leave dissecting the balance to an expert.

“Less than 10% is accounted for by the barrel’s

previous incumbent, then maybe 5% is influenced by the barley

variety, and 5% by the strain of yeast,” says David

Robertson, The Macallan’s Master Distiller. Then the crucial

bit. “10% could be the wash still and 10% the spirit still,

with the influence of the spirit still being divided into 5% each

for the size and shape of the still and 5% for the spirit

cut.” Sounds good to me.

Plans for Pot Stills

Regarding using pressure cookers, Jack cautions ...

I've used them- I hate them. The

pressure release valves ALWAYS leak (fire hazard, and damned

wasteful), thay always come coated in some impossible-to-remove

grease, the places to mount the thermometer is always guaranteed to

give false readings (either high or low, never the same twice).

They are expensive, heavy, the aluminum model pits to easy, and the

steel is to expensive (with the same problems except pitting of the

metal). Don't bother. Get a small keg or 5 gallon drum that's

stainless and food grade- I've seen them for from $20 to $40US. Or

get a milk can (US$100) expensive, but attractive.

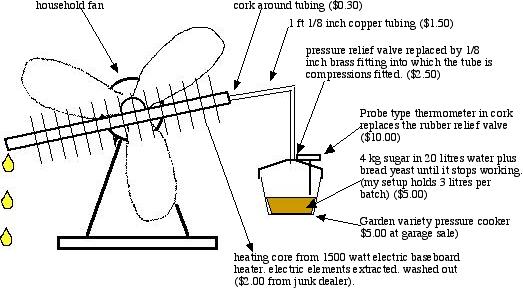

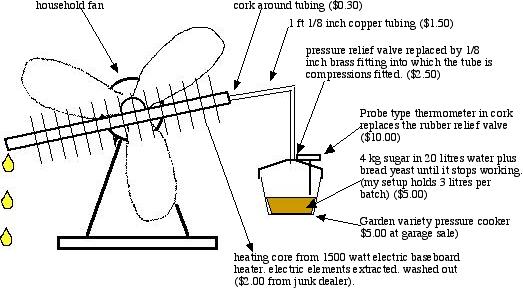

Below is a diagram of Harold B's pot still. Very cheap and easy to

make. Harold suggests that you should adjust the heat so that the

lower end of the condensor can be touched. The reason for this is

that you can see water vapour if things are too hot, but you can't

see the alcohol vapour.

Another great simple design is Geoffs..

Walter describes his pot stills ... "Volodia's Samohonka 1&2"

Inspired by folk stills in Jamaica

and East Africa made from 44gal drums, (see "Alcohol in East

Africa. 1850-1999" - www.dur.ac.uk/History/web/distillhist.htm)

I made an urban version using:

-

- Pot : 5gal (20 L) open top paint container.(These can be

ordered in new from some proprietary paint chain outlets/paint

trade oulets, or get some free from painting contractors and clean

them with paint stripper/turpentine (I have done this before I

found a source for $AUS15 ($US7.50) "Ameron" coatings makes a heavy

gauge container for their industrial coatings. The parent company

is in the U.S. The paint company "Solver" in Australia can get

unused containers through their chain of shops. Container

manufactures sell them quite cheaply but only in lots of 50 (I

enquired). Cleaning free empties is not too difficult. and helps to

recycle them. I know a local owner of a paint store who recycles

them into kid's rubbish bins with appropriate designs on them - why

not something more useful!

- Outlet arm - 1.5m of 10mm (3/8in) soft copper tube, bent to

form a "lyne arm",up 200 vertically & then 600 long inclined

upwards (to get some reflux) and then down 700 vertically. The 10mm

soft copper tube is easily bent without flattening - use salt

inside the tube to help prevent this, standard grommet for plastic

beer fermenters, or improvise using cut sections of synthetic wine

corks glued to both sides( they close in well).

- A 500 long Leibig condenser over the 700 copper tube section

out of plastic T sections (2 x 19mm/13mm (3/4in,1/2in) barbed PVC

Tees) & 500 length of 19mm (3/4 in) plastic tube, clamps,

silicone or epoxy resin, plastic glue.

- Rubber grommets (as for plastic fermenters)

- Plastic tubing - standard 13mm (3/4in) plastic tubing with

plastic tap to hose connector, 10mm tubing for distillate (this

fits on the 10mm (3/8in) copper tube), and for the water outlet

from bucket to sink.

- Gas flame diffuser mat or bain marie (water bath) to get even

heating.

- Thermometer -digital or mercury to measure pot vapor temp. Stop

distilling at 91C (196F).

- Thumper/Doubler - 10 L (21/2gal) paint container, with rubber

grommets for copper tubing.

- Worm condenser variant - 20L (5gal) plastic bucket or cut down

container, coiled copper tubing, grommets.

No welding - just glue, silicone, clamps. All this is sitable for

most kitchen stoves and sinks. Obviously this is an introductory

still for the beginner.Paint tins are not heavily coated. Kept dry

it should last years - rust remover will extend this.

I forgot to mention Safety aspects important as we don't want

kitchens going up in flames! I switch the exhaust fan on to take

away any stray fumes, even though the ring clamp is air-tight. I

made the lyne arm quite long for partial reflux and to take it away

from the stove. The distillate outlet tube goes down to the floor,

well away from the stove. An electric stove might be safer,

although apparently slower.

MooNShiNeR describes his 75 gallon pot-still, doubler and shotgun

condenser below. See Moonshine Still

Photos for a couple of photos of it.

I use a medium sized (75 gal) pot

still with a doubler/thumper (5 gal) and a shotgun condenser for my

purposes. I also utilize a 20 gallon outfit with a 1 gallon doubler

and a worm condenser mainly for running smaller batches and

epecially for running backings or low wines to "up" the proof

quickly.

I use copper sheets soldered with silver solder to build most of my

components. Shotgun condenser made from of an old, antique copper

fire extiguisher. Cut both the ends off and sand everything inside

and out. Clean it to the "eat off of it" stage. Cold water enters

the shotgun condenser from the bottom and exits the top to force

the hot water out and this always keeps the bottom part of the

condenser way-cool.A shotgun condenser is basically a condenser

with a water jacket too cool the steam and it has dozens of 3/8"

copper line that the steam goes through. It's kinda hard to

explain. Where the steam goes through looks like the business end

of a gatlin gun. Bore two holes in the jacket about 3" from each

end and solder a brass hose copper garden hose connector in it, top

and bottom. On the one you use for the bottom, you will put a

spigot used to regulate the amount of cool water coming into the

condenser. On the top one you'll attach a garden hose and lay it

out where the hot water can drain off the top of the condenser. Two

copper sheet circles are cut and clamped together and numerous

holes drilled through them. The circles are placed inside the

copper jacket and spot soldered.(silver) in place with a few pieces

of the 3/8" line in to keep things lined up good. The lines are cut

about 4" shorter than the jacket. Start putting the lines in and

soldering them in place and solder the circles in good, top and

bottom.

On the first run, you'll be able to tell if you have any leaks or

not. you can fix them if it does.

Make a tight fitting cap for the top to be sealed/pasted on with

corn meal and water. The bottom does not require a tight fit at

all. It is just there to collect the alcohol as it comes through

and then out to the jug/bucket. With a shotgun condenser, you can

fire the still as hard as you want to and you'll have no problem

with it not keeping up. That's why people who do volume like them

so much.

A. Nonimus suggests ..

First off - most homemade

potstills in the U.S. are made out of 20 litre pressure cookers

(they have all the fittings you need including pressure release

safety valves)- If this is in fact what is planned, you MUST

remember to NOT PERMANANTLY MODIFY THE PRESSURE COOKER IN ANY WAY

-(remember, 3/8" copper tubing makes a nice coil, and fits the

outlets on most stills!) if the law gets news about you running

your own still- they can (with a warrant- not hard to get anymore,

I'm afraid) raid your place, if they find a pressure cooker with a

bunch of copper tubing attached to it, and holes drilled in it that

are homemade- they will have the evidence needed to take you to

jail for running a still. IF the pressure cooker is always returned

to it's original state (normal fittings and weights) after you

distill with it, and if you put your condensor next to some beer

making supplies (or, rather mash making supplies- same thing)- when

(if) the cops show up, they find a normal (unaltered) pressure

cooker and something you will swear up and down is a wort chiller

for the making of beer. If no moonshine is found- they have

absolutely no case against you.

Second - The average 20litre pressure cooker can be set inside a

large stockpot (the 30 quart or larger models, just measure the

cooker, and go out shopping for a cheap canning pot big enough to

hold it easily). By placing 2 pieces of wood, pipe, etc. accross

the top of the canning pot, the handles on the pressure cooker will

sit on these cross pieces- this will keep the bottom of the

pressure cooker off of the bottom of the canner. Fill the large tub

with water and then fill the pressure cooker/potstill with your

mash and cook with a nice even heat (if using gas this reduces the

fire hazard as well- now the alcohol isn't in direct contact with

the metal touching the flame). This allows you to distill mash that

has a lot of solids (the more gentle heat helps prevent sticking

and burning), it also allows you to do something else while warming

everything up- Just put the water on to boil, and put the canner in

after the heat is where you want it- better temp control- and

unlike the still- you don't have to watch the water heat up (unless

you are bored out of your mind)- just make sure the potstill body

isn't touching the metal of the large stockpot (The "jacket")-

there you go- a homemade steam heated still!

Toms potstill ..The boiler is a 2.5 gallon soda canister. I heat

it by securing it in a pot of boiling water, and run it like a

double boiler. It works great!

Thumpers, Doublers & Slobber

Boxes

Some moonshine stills have a "thumper" or "doubler" between them

and the condensor. This is a jar of sorts, half-filled with liquid

(water, mash or tails). See the Moonshine

Photos for examples of them. There is also an anonymous file on how to

construct a doubler : Doubler.pdf (220kB)

Thumper

This acts as a simple second distillation stage. Once its fully

saturated with alcohol (hence better to start with something

already containing alcohol), and up to temperature, the vapour

leaving it will be doing the equivalent of a second distillation

(usng the incoming vapour as the heat source) (see the wee applet

in Reflux Design ... set it to

2 stages .... so the vapour leaving a 15% wash will be coming off

at 65%, after going through a second stage (the thumper) it will be

at 85%).

Rudenoise's pot still shows an excellent example of a thumper in

action ...

I wanted to start out with a small still and this was the answer.

In a matter of four hours I had a still made, using 3/8 copper

tubing I made a condenser and encased it in a PVC jacket with water

circulating through it. I use gromments to pass the copper coil

ends through, and some brass nipples for a water entry and return,

this is hooked up to a small tabletop fountain pump in a bucket of

water that circulates the water through the jacket. It really works

well. I used the stainless steel cooker. I first primed it (for no

better term) on the stove with water prior to modifying it. While

still warm (cooker) I washed it with soap and water and this took

care of the grease they lubricate the lock with. In addition I

added a "Thumper" or "Slobber Box", using a pickle jar and a couple

rubber grommets (works great), and a hotplate.

How does this work ? I'll try and describe it ...the main pot heats

up, and begins giving off ethanol vapours (say at 40% purity at 96

° C off a 5% wash)... these get passed into the thumper and try

to bubble up through the liquid there. But because the liquid is cold

too, the vapour will all condense if given the chance (e.g. small

bubbles & water deep enough). A bit later on, the thumper liquid

is starting to heat up and increasing in ethanol content .... soon

the thumper is at say 84 ° C, and the ethanol content is around

40% - gees - that sounds like a second pot still doesn't it ? So

the ethanol starts coming coming out of solution, though this time

it will be at around 75-80% - hence the second distillation

occurring - all for free, no additional cost or heating involved.

Of course all this depends on how effective the thumper is at

knocking down the incoming vapour - e.g. bubble size, depth of

immersion, % alcohol in the vapour & thumper liquid etc, but you get the basic idea.

Look at the energy involved ..

Heat of Vapourisation/Condensation

Water = 2260 J/g

Ethanol = 855 J/g

So an incoming stream of 40% ethanol will give up about 1698 J/g,

whereas to vapourise a 75% rich vapour needs about 1206 J/g. Then

given that the flowrate of the 75% product is going to be only just

over half of that entering, you have HEAPs of energy left over, to

first heat the liquid there during the inital phase, then to

superheat the vapour once the thumper is up to temperature. So the

stuff coming in can more than happily look after itself in terms of

redistilling itself.

I have a spreadsheet Thumper.xls

which does these calculations for different scenarios.

Play with the spreadsheet, and test the various scenarios ....

- Thumper vol 1000mL and 0%

- Thumper vol 1000mL and 30%

- Thumper vol 3000mL and 30%

With a small thumper volume, the contents are fairly quickly heated up

towards the liquid boiling point, but its % alcohol is quite low. For this

situation, the vapour then tends to bubble up through the thumper, with no

further enriching. What goes in is what comes out - no real increase in

purity. The extreme case is one where the thumper acts to strip alcohol

from the vapour, and produce a lesser strength vapour.

This situation changes a little if the small thumper is initially charged

with a liquid of high % alcohol - eg the tails from the last run, say at

30-40%. In this case, the excess energy available is sufficient to cause

the thumper to act like a second distillation stage - once its up to the

boiling point of the % alcohol in there, the energy goes into vapourising

the vapour there, producing an output quite a bit higher in % than the

vapour entering from the pot still. Unfortunately, because of its small

volume, this isnt sustained for too long, all the alcohol is driven off,

and past a particular point in time, the thumper then simply lets the

vapour bubble through & do nothing further, if not actually stripping the

vapour & producing less than that off the potstill.

The best scenario for the thumper is where it is of quite a large size, and

charged initially with a reasonable % alcohol. Even starting it with the

same % wash as that in the pot still is an advantage. In this case, the

excess energy from condensing the pot still vapour goes into releasing a

vapour of quite a high % alchol, always higher than that exiting the pot

still. In this scenario, the thumper is a benefit, as it allows quite an

enriching of the vapour to occur, with no additional energy required. The

only condition is that the thumper is charged with a liquid of a reasonable

% to begin with - if simply filled with water it wont work.

To make the thumper effective you want

- lots of vapor liquid contact, ie heaps of small bubbles - eg

use a screen or simply lots of pinholes in the bottom of the inlet

tube.

- the liquid in the thumper to begin high in alcohol, so a small volume of wash or, maybe

better, tails from the last run. Deb recommends .. You put tails or mash into the

thumper - not water - and the loss is not a factor compared to the

resulting alcohol content :) I highly recommend a thumper!

- larger is beeter than smaller. For sizing a thumper, Ted suggests ..

A good rule of thumb is make the

thumper twice the size of the amont of distillate in a single run.

ie: one run = 1 liter of spirits then make the thumper 2 liters

.... as a minimum, have it at least 1/3 the volume, ie ((#gallons

of wash * %alc of wash) / 3), or if using tails in the doubler,

((gallons of wash * %alc of wash + gallons of tails * % alc of

tails) / 3). I myself prefer to use a larger size to allow for

condensation that always seems to overflow the thumper. My

grandfathers still was 250 gallons and had two 50 gallon thumpers

as well as a 50 gallon slobber pot.

Jim writes ...Run your doubling keg in a water bath makes a good drink and it's pure. Do not add no liquid it makes it's own liquid

Note that thumpers aren't the same as slobber boxes (although they

look fairly similar. The inlet in a slobber box doesn't extend down

into the liquid, so no bubbling & hence further distilling

takes place. Rather, it just provides a place for any rubbish (ie

foam, mash etc) pushed up the neck of a pot still to settle out

before entering the condensor. They sometimes have a small drain

cock on the bottom of them to help empty them while the still's

running. The original purpose for a slobber box was for stills heated

by a fire beneath them - if the heating got too vigorous, and the contents

foamed or bubbled up into the lyne arm, that it would settle out in the

slobber box rather than go and contaminate the main spirits being collected.

They're not needed on well controlled stills.

Slobber Box

Double Walled Boilers

Joe writes:

Single walled bottom still designs are good only for sugar mash

distillation and unsuitable for distilling thick mashes or preparing

absinth.

With direct heating, and especially with internal heating of keg,

local overheating can (and will) occur for highly viscous mashes

(grappa, plum, apricot, apple, quince, etc.). The decomposition

(burning) of mash produces a terrible taste and smell, hard to

remove. If you try to polish the distillate, fruit taste and smell

will disappear first.

It is a rather easy task to transform a keg to a safe, dual purpose,

water bath type double bottom boiler.

Generally a keg consists of the vessel itself, there is a lower

and an upper skirt. Skirts are most cases welded to the vessel. If

you close the lower skirt with a flat head (e.g. a 1/16"ss plate)

and patch the went holes, you get a lower vessel for the water bath.

For joining the head TIG, MIG or stick welding is best, but brazing

is also possible. Patching the went holes you may use welding or

brazing. Drill a ¼" hole on the side of lower vessel. Attach

(braze) a ¼" pipe to the hole and have it run vertically to the

top of the keg. Lace it through the upper skirt through a went hole

and bend it to vertical position. Attach a proper safety valve

(e.g. a weight type for pressure cooker ) on the upper end of pipe.

When selecting the type of safety valve you have to consider the

danger of implosion during cooling. At 180 degree from the ¼" pipe

(on the opposite side of lower vessel) drill a ¼" hole and braze

over the hole a ¼"nut. Close it with a heat resistant gasket and a

¼" flat head screw. This will be the bleeder. Perform bubble test

on joints.

Filling: Remove the weight of safety valve, screw off the bleeder.

Fill up the lower vessel through the safety valve body and ¼" pipe

using a plastic hose. When water starts to flow from bleeder, stop

filling, reinstall safety valve weight, fasten bleeder screw.

During distillation process water bath temperature will be in the

lower vessel slightly above 100 Celsius due the minor overpressure,

but this has no detrimental effect.

Check water level in lower vessel each time before using, by shaking

the keg. According my experience refill is rarely needed.

Annually descale lower vessel with vinegar. In case of using the keg

in cold climate avoid freezing the water.

I have been using this construction for years without problem,

quality of distillate improved dramatically.

Of course, if you distil thick mashes a greater opening ( min. 6"

diameter) is needed to fill and clean the keg.

Gin Heads

David writes ..

A Gin head is a large separate

compartment that sits above the boiler on a gin still in which the

botanicals (juniper berries, coriander etc.) from which gin gets

its unique flavour are placed and through which the the alcohol

vapour must pass before it enters the column. As such gin stills

are pot stills rather than reflux. They are still specifically

designed for making gin although they are and can be used for

making other similar drinks. As such they have mostly been made by

one British company for the last two centuries although I dare say

there are now other companies that make similar stills elsewhere.

Steam or vapour distillation is better at extracting essential oils

and other more soluble components as compared to steeping which

tends to extract tannins, phenols and the more harsh bitter

components.

UPS adds ..

A gin head still is a pot still

that has a basket like arrangement just at the start of the "lyne

arm" (the part of the condensor coil that is coming out of the top

of the boiler, but has not yet entered the cooling tank yet). In

the basket goes the botanicals that turn what is essentially a

vodka into a gin. This is the method that Bombay uses among others,

and is thought to give a more delicate style of gin. Nothing really

fancy, just a basket sitting on top of the boiler before the

condensor- if you lookat some commercial distilleries pics, you

often see a swollen bulb at the top of the still where the

condensor line runs out from - if a basket arrangement was put

there it would be a gin head still - appearantly, many scotch

distilleries use a gin head still - they just don't put any

botanicals in it. This is a holdover from the days in England when

gin was the most common (cheap) drink to be found- when gin's image

crashed the scotch distilleries bought the surplus

stills.

Ted also adds ..

A gin head is a pot or column that

steam travles through enroute to the condenser. A thumper works

rather well. Just pack it with the herbs and run clean drinkable

60% ethanol in your still for gin. Pack it with peppermint to make

schnappes. Pack it with... well you get the picture. Put just water

or varying amounts of ethanol in the still for making oils from

mint or whatever has an oil contenet.

Condensers

I have done a wee interactive calculator to help with sizing condensers.

Andrew advises ...

One of the easiest ways to

increase a heat trasfer coeficient is to increase the velocity of

the fluids. Temperature of the cooling medium helps, but velocity

is MUCH better. This is why blowing on a spoon full of soup with

your breath (about 90degrees F) cools it off much quicker than

holding it in front of your nose, even on a chilly morning. What

I'm getting at is that close clearances are desireable, as you will

get lots of heat tranfer into your cooling water.

A good design, utilising this is Tom's version, used in a

Nixon-Stone settup - see here

for his diagram.

If you're wanting to make a condensor coil, like the Nixon-Stone

style ...

Paul offers ..

if you are going to bend copper,

get a tube bender. This is a wound steel spring that allows you to

bend tubing without kinks. Your hardware or plumbing supply can

help.

and John ...

Spring-benders while they aid in

crude tube bending can be replaced with a die and mandrel type of

bender. This will yield uniform bends.These benders are available

from "Imperial Eastman Co." For larger diameters anneal the bend

area, cool,pack with sand and form over wooden die that has been

fabricated to match bend radius. This procedure will elevate the

finished product above the amateur level.

You just need to evaluate if the extra cost is worth the extra

quality.

Jack suggests ..

A fancy mandrel type of

arrangement is easier to get than you might think - most people in

this area just wind the copper tubing around an old paint can. It

works a lot better than doing it by hand or with a spring tubing

bender. Past about one half an inch in diameter it gets to be a

little hard to do.

Another approach is to air cool the distillate. "Vonmantik" writes

..

I had the fortune of befriending

an old distiller from the smokey mountains who had a ten liter

cooker with reflux tower. The unusual part was that he had designed

a air cooled condenser. It was made of about 25ft of 3/8 copper

tube coiled tight and centered in about 4ft of pvc pipe, on top was

a small box fan (from a recycled computer) that drew air through

the pipe. Intake was controlled by a homemade collar with allowed

the operator to contol air flow. This an idea that can be expanded

on it there is a problem plumbing water to the place you want to

set up.

Homer has a diagram of how he has fitted the coils into his reflux

column. Click for a larger diagram :

Walter describes the "gattling gun" condensor ...

I noticed that the N-S stills have

a coiled vapor condenser consisting of 3m of 5mm tubing through

which water flows, and from comments seems inadequate. What about

using a mini shot-gun condenser? On a typical 50mm diam. column

this would mean say a 300mm length of 50mm tubing, with a plate on

both ends with 12 holes drilled in a geometric pattern to take 12,

5mm open-ended tubes welded in place. It is still open to the sky

for safety. On the side there is a water inlet at the bottom and an

outlet at the top for the cooling water. In effect we have 3.6m of

vapor in 5mm tubing surrounded by cooling water rather than the

other way around. The unit can be welded on the top or attached by

a standard 15mm threaded plumbing connector so that it could be

replaced if necessary.

Vacuum Stills

Using a vacuum allows the use of lower temperatures, and can attain

higher alcohol concentrations, eg at 42 mm Hg (cf 760 mm Hg =

atmospheric pressure) the column only need be at 35 C (ie just use

hot tap water to heat with). The azeotrope (the point where

distillation ceases to work because the vapour and liquid purity

are the same) moves towards 100 % as the pressure is lowered; below

0.1 atmospheres it disappears, allowing you to distill all the way

to 100% alcohol (provided you beef the reflux ratio up to >20).

They can also be more energy efficient, and allow for a greater

capture of the available alcohol. The lower temperatures also mean

that they're use a bit in the distillation of essential oils (which

would be otherwise be broken down at higher temperatures).

The graph below shows the reduction in temperature. I'm not

quite happy yet with my calculations for this (the Textbook & 1

Atm lines should be the same), so don't go and design from it, but

you can see the basic principle at work ...

To create a vacuum, you can either use a mechanical pump, or a

a venturi ejector (water jet pump). The venturi ejectors (vecktors) are commonly used

by laboratories etc to assist with filtering material. They just use

flowing water to create the vacuum, and cost around US$20.

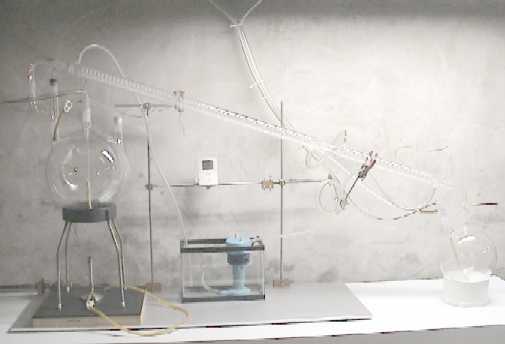

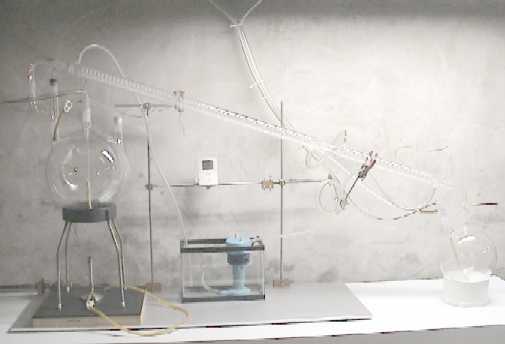

Joel describes his vacuum still

Not only is it all lab glassware

with ground glass connections....but the entire system runs under a

25"Hg vaccuum. The vaccuum makes the whole process much more

eficient and keeps the boiling temps very "true". The vaccuum is

also used to change batches without having to take anything

apart.

The tank in the picture is the main coolant resivior. I built a

cooling tank that sits outside and uses the cold winter ambient

temperatures to chill the coolant. It consists of a 35 gallon

garbage can with 125 feet of copper coils inside. The can is filled

with automotive anti-freeze and the little pump in the pic pumps

winshield washer fluid through the closed loop copper coil system

and then through the condenser coils in the picture. On a really

cold winter day....I can get a 100 deg. ambient drop between the

inlet and outlet ports on the chiller.

After distilling the "product" 6 times and paying close attention

to the temperatures (to make sure all the methanol has been

separated from the "good stuff") I end up with distilate at 180

proof that WILL NOT give you a hang over.

Ólafur describes his vacuum still ...

My pot is around 60L. It is

enclosed in a rather large plastic barrel and I heat the system

with hot water. The water is around 80C so I don't need a lot of it

and, besides, it doesn't cost a lot here in Iceland. The column is

2" X 60cm SS packed with ceramic rings. The water for the jector I

let straight through so as not to create resistance on the out end.

The cooling water I let in at the bottom end... The jector suck out

of my collecting jar which is in turn connected to the condenser so

any vapour rising up the column has to go through the condenser

before it gets to the collector before it gets through to the

source of the vacuum. The cold water in iceland is somewhere around

4-5 C so cooling is not a problem.

Note that in most cases, the vacuum is applied to the distillate

collection container, after the condensor. This way there is little

loss of vapour from the process, and there doesnt need to use much

vacuum. Many of the comments below are concerning the setup where

the vacuum is applied to the vapour line.

There are several problems with Vacuum stills though:

- you can lose some alcohol vapour out through the vacuum

pump,

- you must have an accurate measure of the vacuum applied (not a

big problem, one of the reasons the still is not easy to

build),

- its hard to find leaks (thus requires care during

construction),

- very low vacuums are difficult/expensive to attain (but

generally not required - only a small vacuum is needed), and

- the low temperature can make it difficult to recondense to

vapours (need realy cold cooling water & enough condensor

surface area)

Often the vacuum can be made by using a "Venturi" or "Vektor" which

uses the cooling water, and causing it to go through a small nozzel

increases its velocity. This causes a corresponding decrease in

pressure, and hence can "suck" vapour from the still. However, this

can eject some vapour out of the system.

The heating can be a simple water jacket around the pot, using hot

tap water.

What can also be confusing is when the mash begins to boil, the

vapours will expand into the vacuum space, and your gauge may go

back to zero. This doesn't mean you've lost your vacuum, but if you

can have some of your still appliance in glass or plastic so you

can see what is going on, this helps so you know you have some

action and not a leak.

One of our visitors is in the process of working on an improved

vacuum still design. We'll keep you posted once he's happy with the

results (including maybe a photo, design, info, history &

performance.)